Paolo Parisi

Mostra personale.

Comunicato stampa

IL PUNTO DEI PUNTI DI VISTA di Paolo Parisi

Il punto di vista che ci offre l’arte di Paolo Parisi è che essa non sia un mezzo di pura espressione, ma soprattutto uno spazio dell’esperienza umana e del suo punto di vista. Modo di vedere che di volta in volta si focalizza sui fenomeni visivi che ci aiutano a comprendere la nostra collocazione e condivisione nello spazio del mondo. Parisi con le sue opere, principalmente quadri, ci fornisce dei dispositivi ottici che ci aiutano a guardare diversamente la relazione col nostro spazio che può andare dal territorio alla particella. Premettendo che nello scrivere dell’arte e degli artisti, a mio modo di vedere, metto sempre un po’ di biografia, dirò che Parisi è dal 1965 di Catania, essendovi allora nato e cresciuto, finché non decide di andare a studiare all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, dove da studente è finito per diventare insegnante nella stessa scuola. Questo di Parisi è stato un viaggio di conoscenza ed esperienza compiuto da molti altri in periodi diversi per confrontarsi non solo con la storia dell’arte moderna e contemporanea, ma con tutta la storia, dato che Firenze è la culla del rinascimento e non solo. Qui il confronto diventa a tutto campo con l’intero arco dell’arte intesa come pittura, architettura e scultura. Si tratta di un percorso formativo che prima e dopo Parisi ha attratto artisti da molte parti, come ad esempio la corregionale Carla Accardi da Trapani pure lei formatasi a Firenze anche se poi riparata a Roma, città eterna, in cui ha sviluppato la sua pittura disegni. Un’arte di segno anch’essa in dialogo con l’architettura come dimostrano le sue tende, coni e cilindri in sicofoil dipinti. Dicevamo che in questo tragitto formato e formante Parisi ha finito per arricchire la sua esperienza di partenza con quella di destinazione, mescolando così le culture manuali e concettuali, due dati fondamentali su cui si basa la sua produzione artistica; una dualità nell’unicità specifica di Parisi sottolineato anche dagli artisti. Siccome lo sguardo degli artisti è sempre fondamentale per leggere le opere d’arte, soprattutto quelle degli altri, credo che mi baserò anche su queste categorie per offrirvi il mio, o i miei punti di vista su Parisi e la sua opera.

Inizio col cercare di spiegare cosa vogliono dire queste osservazioni mosse da campi opposti; diciamo che si tratta di opere che, in un certo senso, scontentano, non mettono d’accordo le categorie e che quindi sono opere critiche, attivatrici di pensiero oppositivo che non è cosa da poco in momento in cui si sente il bisogno di un’arte che ci aiuti a riflettere sul nostro essere nel mondo. Per questo egli lega la sua opera alle utopie moderniste, anche se momentaneamente “fallimentari”, tipo le Unité d’Habitation di Le Corbusier, a dire dell’architetto progetto di residenza collettiva ispiratagli fin da giovane dalla Certosa del Galluzzo di Firenze. Come vedete, le strade dell’arte e dell’architettura portano a Firenze, perché ricca di suggerimenti capaci, in questo caso, di coniugare la vita privata con quella collettiva.

Ma si dirà: cosa c’entra l’architettura con la pittura?C’entra per vari motivi: primo perché per la generazione degli artisti di Paolo Parisi l’architettura era un punto centrale intorno a cui far ruotare la poetica dell’opera d’arte pittorica che doveva sganciarsi dal Neoepsressionismo duro e puro degli anni ottanta. Parlo di autori diversamente pittori come ad esempio Michel Majerus, Franz Ackerman, Manfred Pernice. Ecco, come loro, Parisi è diversamente pittore, vale a dire che usa la pittura in modo apparentemente improprio e la discute con l’architettura e a volte anche con il design. Infatti, proseguendo nel campo dell’architettura e del suo rapporto con la pittura, è noto che sin dagli esordi essa è stata il supporto primo e privilegiato della pittura: dai graffiti delle caverne ai templi greci e alle case romane dagli affreschi medievali a quelli del rinascimento e così via. D’altra parte, la stessa Certosa del Galluzzo contiene affreschi straordinari di Pontormo, un artista che ha usato il colore in modo improprio, colore che, guarda caso, ritorna in certe opere di Parisi.Firenze è il luogo in cui questo incontro si è forse più focalizzato e dibattuto nella storia come scrive Vasari già nel 1550 nel sue noto libro Vite dei più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori. Si tratta di un volume sull’arte preceduto, sempre a Firenze, dalle teorie di artisti come Cennino Cennini che si definiva “piccolo maestro esercitante nell’arte dipintoria”, il quale, agli inizi del XV secolo, pubblica Il libro dell’arte o il trattato della pittura, mentre un po’ più avanti troviamo Leon Battista Alberti con i suoi De Pictura, 1435, e De Re Aedificatoria, 1452. Il primo, quello che parla di pittura, è, però, dedicato a Brunelleschi che non era pittore, ma architetto e scultore. Tuttavia, questa dedica è rivelatrice proprio dell’importanza della relazione tra la pittura e l’architettura e la relativa invenzione dello spazio simbolico; vale a dire la prospettiva a punto di fuga unico che Brunelleschi aveva inventato a utilizzo di tutti, ma soprattutto dei pittori. Questa relazione tra mestieri si evince dal rapporto dell’Alberti, anch’esso architetto, con Brunelleschi che riconduce anch’esso teoricamente tutto alla pittura.

In un simile contesto, dove l’arte di questi maestri è fortemente presente nella città, l’artista Parisi non poteva non sentire la necessità di un confronto anche se indiretto, affrontando questioni che oggi parrebbero andate, ma che invece, per l’arte, non lo sono mai. Ciò accade a partire dalla possibilità, in un mondo “informe”, di utilizzare ancora la prospettiva, vale a dire la possibilità di guardare al mondo non per quello che è, ma per ciò che l’arte propone dovrebbe essere.

Tale attitudine allo sguardo è presente già nella prima opera che incontriamo entrando nella mostra della galleria Massimo Ligreggi: Da cima a fondo (predella), 2011. Si tratta di un polittico a pannelli di legno che rimandano alla pittura su tavola medievale: sono quattro tavole affiancate su cui troviamo dipinti dei segni informi grigio-argento,segni che creano immagini più somiglianti a isole in un mare di legno che a rilievi montani. Si tratta di segni della pittura risultanti dalla visone dall’alto di immagini riprese dal finestrino dell’aereo durante vari viaggi a volo d’aeroplano, forma moderna della prospettiva a volo d’uccello cara a Leonardo, altro riferimento di Parisi. La pittura-segno dell’opera delinea le cime dei monti, le sommità, compresa quella dell’Etna e dunque della vallata catanese. Il riferimento alla predella poi sta nella collocazione inusualmente bassa dell’opera in riferimento alle predelle che nelle chiese sono collocate nella parte bassa del polittico e dunque più vicino all’osservatore.È, dunque, un modo antico e contemporaneo di parlare del punto di vista dell’artista, primo osservatore, che spinge a favorire il nostro vedere, da quando, all’inizio del Novecento, il punto di vista dell’altro è entrato a far parte dei discorsi sull’arte; una possibilità sottolineata anche dalla tradizione filosofica ermeneutica che va da Walter Benjamin a Eco a Gadamer fino a Jauss.Ruotando nella sala, a seconda di dove direzioniamo lo sguardo, notiamo opere pittoricamente “più strutturate”, quadri “astratti geometrici” di cui non possiamo fare a meno di notare la fattura realizzata tramite pennellate, soprattutto ortogonali e diagonali, sovrapposte come The Whole World in a Detail, 2019, dove il confronto è con la realtà virtuale. Qui il quadro si presenta come una scacchiera multicolore che rimanda alla pixellatura ingrandita delle immagini digitali, quadratini atomi delle immagini della figurazione contemporanea. Con questo modo di lavorare l’artista continua il suo andare a fondo delle ragioni costruttive delle immagini, ma soprattutto della pittura e del suo farsi. Il farsi della pittura in quest’opera è centrale, perché i tanti quadrati di colore diverso sono realizzati dipingendo a spatolate di colore sovrapposte ortogonalmente: prima dall’alto verso il basso, poi da destra verso sinistra e viceversa. Si tratta di presentare la virtualità del digitale, dunque l’assenza del corpo, con la presenza lenta e continuata del gesto umano ripetuto, volto a creare una pittura fisica fatta di molti strati; un corpo a corpo con la pittura che si inspessisce, diventando quasi scultorea.In questo principio oppositivo, che porta alla formazione di opere ricche di contraddizioni e quindi di contestazioni e controversie produttive “la trama sovrapposta domanda: Cosa stiamo guardando? È un'immagine bidimensionale o tridimensionale? È un'immagine che rappresenta qualcosa o è un'immagine astratta? Si tratta di tecnologia o tradizione, fisicità o immaterialità? (Parisi).

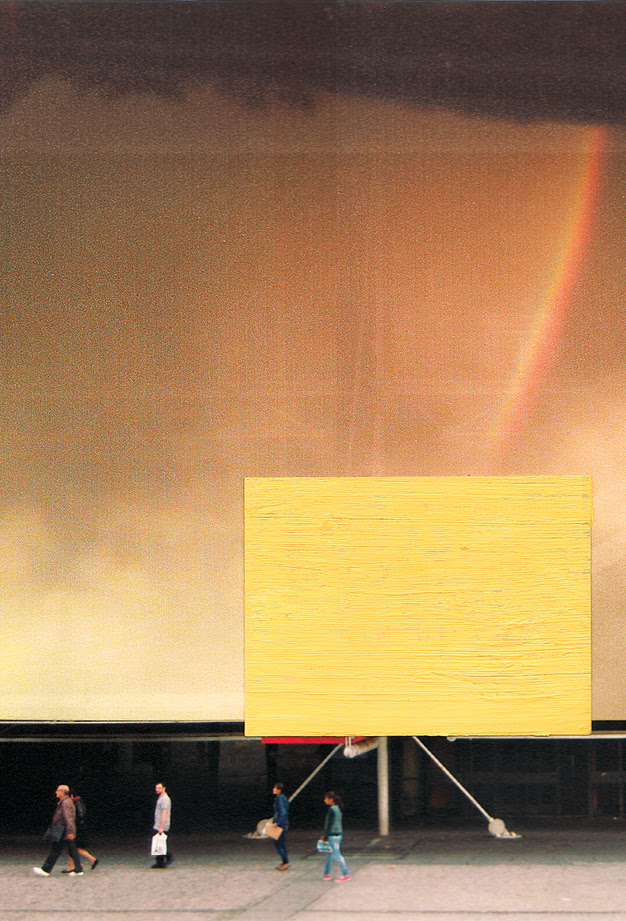

Domande ad alcune delle quali abbiamo già risposto, altre a cui cercheremo di rispondere, iniziando col dire che le modalità operative dell’artista Parisi sottostanno al principio generale della relazione modernista che si basa, soprattutto in architettura, sull’ortogonalità che sappiamo essere non solo un mezzo pratico, ma, al pari della prospettiva, una teoria di conoscenza del mondo. Teoria e pratica che ritroviamo pure in The Whole World in a Detail (fabric), 2019/2022, un trittico azzurro, nero e verde anch’esso realizzato per strati pittorici la cui superficie, cromaticamente sontuosa, rimanda alla preziosità dei tessuti di abiti e tendaggi dipinti nei quadri del Rinascimento. Anche qui non c’è figurazione, ma il concentrarsi su un particolare ed esaltarlo nel suo aspetto cromatico con spatolate diagonali rivela, ripetiamo, non un discorso sulla figurazione, e dunque sulla rappresentazione, ma sull’analisi e presentazione della pittura che è un dato fortemente concettuale.Non dimentichiamo poi che sul principio dell’ortogonalità cartesiana dura e pura si sono dibattute teorie della pittura astratta moderna del XX° secolo e che su questo si sono rotte delle amicizie come quella tra Mondrian e Van Doesburg in quanto quest’ultimo a un certo punto introdusse la diagonale nella pittura De Stijl, motivo per il quale Mondrian gli tolse il saluto. Per fortuna da allora tanta acqua è passata sotto i ponti così che oggi Parisi può indifferentemente utilizzare diagonali, ortogonali, linee curve e così via, perché il suo non è solo modernismo, e concettualismo, ma anche pratica pittorica attiva. Difatti, dipingere una stoffa, proprio per le sue qualità di preziose luminosità e morbidezze, nel Rinascimento, e non solo, era uno degli esercizi più difficili allo stesso modo in cui lo era l’incarnato dei corpi delle persone e dunque anche metodo di valutazione della bravura del pittore, nonché di costi. Così pensiero, tecnica, economia, spazio confluiscono a dare sostanza all’arte in questione, operazione tanto importante in quanto rappresentata con forme astratte che sollecitano il nostro sforzo interpretativo, richiedendo una non passività dell’osservatore, a cui si chiede un parere a dare un suo punto di vista. Infatti Parisi, primo osservatore per assenza delle sue opere, è come l’assente Lorenzo Lotto guardato dal giovane che ritrae, sul quale si è concentrato Giulio Paolini nel suo Giovane che guarda Lorenzo Lotto. Perciò Parisi ci da, come dicevo, opere che sono dei meccanismi ottici come nell’altra opera qui presente Unité d'habitation del 2016,il cui titolo evidentemente rimanda al già citato Le Corbusier e alla sua utopia che era, oltre che un progetto dell’abitare, una teoria del vedere, nonché del colore che del vedere fa parte; tutte questioni dibattute durante il modernismo. Le Unité d’habitation sono moduli di appartamenti costruiti su due livelli, abitazioni dalle quali non è possibile vedere la casa dell’altro e quindi non condividere visivamente l’esistenza è un antipanopticon bentaniano da dove era, invece, possibile vedere tutto, al contrario qui lo sguardo è riservato non più pubblico ma privato, mentre la parte pubblica è lasciata all’en plein air del terrazzo e, dunque, allo spazio collettivo confinante con il cielo. Dal chiuso all’aperto e dallo spazio al colore anche quest’ultimo vive la condizione pubblica delle tinte della facciata e quella privata dei colori dell’interno degli appartamenti. Si tratta di un’attenzione di Le Corbusier per la pittura e, in quanto pittore egli stesso e facente parte del Purismo, volto a portare avanti l’idea de l’Esprit Nouveau per cui quest’architettura, come quella albertiana e brunelleschiana, non parla solo della disciplina architettonica, ma anche della pittura. È la condizione del vedere e del nascondere che troviamo nei ragionamenti pittorici presenti nelle opere di Parisi come il citato quadro Unité d'habitation del 2016, opera che gioca sull’idea del vedere e del celare. Sull’idea del vedere e del nascondere, come sull’idea dell’autorialità della forma dell’arte, agisce già Coast to coast, 2007. In questa le stesure di colore diverso, olio sotto e acrilico sopra, generano un’opera viva che continua a farsi da sé, in quanto l’olio sottostante trasudando lentamente crea delle “macchie” di colore affiorante diverso e dunque continuamente un quadro differente. Si tratta della questione dell’opera aperta in cui significato e forma, autorialità e co-autorialità sono in divenire, mai finite. Alla fine, però, e come già detto, territorialità, geografia, spazio e altri temi che l’artista affronta a partire dalla prima opera tornano anche in lavori come Bench for Everybody, 2004, opera praticabile, al centro della stanza. Si tratta di una seduta in strati di cartone dove l’ortogonalità è interrotta dalla sagomatura di linee curve che incontrano quelle dei morbidi corpi delle persone che possono sedervisi sopra. Qui l’architettura, si fa scultura, incontrando il design radicale di cui Firenze è la patria e dove il modernismo si infrange in parte sul postmodernismo e in parte sulla neomodernità. In questo diventare scultura dell’architettura evidentemente si inserisce anche l’altra sua opera: i “modellini architettonici” U.s.a.i.s.o., 2009>2013, acronimo di (Uno sull'altro in senso orario) realizzata sempre in strati di fogli di cartone con calchi degli stessi in gesso, quale antico processo di riproducibilità tecnica infinita. Si tratta di modellini che tali non sono, perché intesi come sculture ambientali, luoghi in cui le varie aperture, porte finestre e soffitto, alludono alla possibilità di guardare verso l’esterno: il paesaggio. Sono sculture e modelli che possono assumere anche dimensione ambientale come quello per Observatorium al Museo Pecci, 2004, in cui si sottolinea ulteriormente la relazione con l’architettura, il territorio e lo spazio.Posti sulla mensola della finestra della galleria questi modellini-sculture sono le prime opere a incontrare la luce rossa dei vetri colorati da un filtro in grado di diffondere gradazioni diverse di rosso che, a seconda dell'angolazione della luce esterna, nel corso della giornata variano il colore della stanza. È una variazione cromatica che colora tutta la sala, e che, andando dal rosso al violetto, rinvia ai limiti entro cui il nostro occhio percepisce tutti i colori.Sono sempre i colori a fare da guida e confronto nella seconda sala, dove sulle quattro pareti campeggiamo altrettante opere. Si tratta di dittici che affiancano una foto con un quadro. Qui l’ambiente si amplia ancora prendendo a soggetto il mare dello stretto di Messina, dunque si tratta di un’arte fatta tra e con Scilla e Cariddi; e se, come mitologia insegna, si supera questo contesto si può superare tutto. Infatti questi lavori sono esemplari: dittici intitolati The Weather Was Mild on the Day of my Departure, 2018/2021, ispirati a un capitoletto del libro di Joshua Slocum, Il giro del mondo di un navigatore solitario. È il racconto di una persona che si trova sola davanti al paesaggio del mare, e qui non sfugge il paragone con l’artista quale essere solitario entro il mare aperto dell’arte. I dittici in questione sono composti da un’immagine fotografica a sinistra scattata dall’artista ogni volta che si reca in Sicilia via mare e un quadro monocromatico a destra. Sono selezionate dalle innumerevoli immagini riprese dalla nave-traghetto nel tratto dello stretto di Messina, foto del paesaggio di mezzo tra due sponde, fra la penisola e l’isola e quindi in un territorio dittico. Sono foto poi selezionate dall’artista e accostate aquadri monocromatici indipendenti, ma il cui colore è scelto per qualche riferimento, o relazione trovate nella foto, o per qualche particolare presente in entrambi. Entrambi costruttori del punto di vista dei punti di vista di Parisi e del nostro.

Giacinto Di Pietrantonio

We have the pleasure to invite you

on 23 June 2023 at 6.00 p.m. to the inauguration of the exhibition :

Paolo Parisi

The problem of sharing available space in relation to the colour of painting....and atmospheric dust.

With a text by Giacinto Di Pietrantonio

-

THE POINT OF (Paolo Parisi's) POINTS OF VIEW

Simply put, the point of Paolo Parisi's art is that it's not just a pure means of expression. More than anything else, it offers space to human experience and the human's point of view. It's a way of seeing focused on various visual phenomena that lets us understand where we stand and what we share in the space of this world. Parisi's works, mostly paintings, are optical devices that help us view our relationship with the space we occupy in different ways, regardless of whether we're considering vast territories or tiny particles.

Writing about artists and art, I always feel the need to start with the minimum background information: born and raised in Catania, Paolo Parisi attended the Fine Arts Academy in Florence. Arriving as a student, he ended up staying as a teacher. As many other artists in the past, Parisi's journey in search of deeper knowledge and experience brought him not only up against the history of modern and contemporary art but the history of the world as well, given that Florence was the cradle of the Renaissance and much more. Here, he faced the full range of art intended as painting, architecture, sculpture. Parisi was not the first or last to be drawn to this path of training that has attracted artists from all over, such as his regional colleague Carla Accardi from Trapani, who also studied in Florence, even if she later repaired to Roma, the Eternal City, where she developed her painting and drawing further, an art made of signs that also addressed architecture, as may be seen by her curtains, cones and cylinders painted in sicofoil transparent acetate. We said that along this trained and training journey Parisi ended up enriching his initial experience with the heritage of his destination, blending manual skill with conceptual depth, the two foundation points on which his artistic production stands, a duality in Parisi's specific uniqueness also emphasized by other artists.

Because the gaze of the artists is always crucial in reading any work of art—especially those of others—I think I'll rely on these categories to offer my own point(s) of view on Parisi and his work.

Let me begin by trying to explain what these observations from opposing quarters say. The works are in a certain sense, disagreeable, in the sense that they do not put the various categories of artists into agreement, and therefore they are critical works, catalysts of oppositive thinking. This is no small feat in times like ours when art is needed to help us reflect on our place in the world today. Perhaps for this reason his works are linked to modern utopias, even those that appear momentarily as "failures", like Le Corbusier's Unité d’Habitation, a collective residence project inspired by the Carthusian Monastery in Galluzzo, Florence, the architect had first seen as a youth. As exemplified here, the paths of art and architecture converge thanks to the abundance of suggestions the city offers, in this case, in the way it blends private life with community living.

Architecture and painting have several things in common. First of all, for the artists of Paolo Parisi's generation, architecture was the body around which the poetics of pictorial artwork was meant to orbit after first breaking loose from the hard-core Neo-Expressionism of the 1980s.

I refer to artists who were diversely enabled painters such as Michel Majerus, Franz Ackerman, and Manfred Pernice. Like them, Parisi was a diversly enabled painter, meaning that he used painting apparently inappropriately, pushing it into a discussion with architecture and sometimes even design. Considering the question of architecture and its relations with painting further, architecture is known to have been painting's first and privileged support since the outset: from cave wall drawings to Greek temples, from Roman houses to frescos for Medieval and Renaissance villas and so on. Hence, the Charterhouse of Galluzzo above hosts extraordinary frescos by Pontormo, an artist whose inappropriate use of color just so happens to return in certain works by Parisi. Nowhere was this encounter ever debated more fiercely than in Florence, as Vasari wrote already in 1550 in his famous Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. This volume on art was preceded, always in Florence, by the theories of artists such as Cennino Cennini, who called himself a "little master practicing the art of painting and published The Book of Art or the Treatise on Painting" in the early 15th century g. Also writing at the time were Leon Battista Alberti with his De Pictura, 1435, and De Re Aedificatoria, 1452.

The first text deals with painting but is dedicated to Brunelleschi, not a painter but an architect and sculptor. Yet the dedication is revealing, precisely due to the importance it gives to the relationship between painting and architecture and the corollary invention of symbolic space: the single vanishing point perspective that Brunelleschi had invented for everyone to use, by painters, above all. The bond between the two arts is reflected in the relationship between Alberti, an architect himself, and Brunelleschi, who also theoretically traced everything back to painting.

In this city where the art of the masters can be seen at practically every turn, the artist Parisi had no choice but to address—albeit indirectly—questions that may seem to be irrelevant today but for art, never are. Having a "formless" world before him, he did this by starting with the possibility of continuing to use perspective, or rather, the possibility of looking at the world not for what it is, but for what art proposes it should be.

This approach to the artist's gaze is already evident in the first work we encounter upon entering the show at Massimo Ligreggi Gallery: Da cima a fondo (predella), 2011. This polyptych on wood panels hearkens back to medieval panel painting: four panels side by side hold shapeless, painted silver-gray signs that create images more similar to islands in a sea of wood than chains of mountains. These painterly signs evoke the view to be seen from an airplane window, a modern version of the bird's eye view dear to Leonardo, Parisi's other reference. The painting-sign of the work outlines mountain ridges and summits, including Mount Etna and therefore the Catania valley.

The reference to predella/dias develops by positioning the work at lower height than where the polyptych would be placed on a church's altar-step, therefore, closer to the viewer. The gesture amounts to a simultaneously ancient and contemporary way of referring to the point of view of the artist, the first observer, that favors our viewing, given that point of view (of the other) has been key to art discourse since the early twentieth century and one whose various possibilities have also been emphasized in the hermeneutic philosophical tradition ranging from Walter Benjamin to Eco to Gadamer to Jauss. As we turn through the room, depending on where we direct our gaze, we notice pictorially "more structured" works, "geometric abstracts" of which we cannot help but notice the workmanship of overlapping, primarily orthogonal and diagonal brushstrokes, such as in The Whole World in a Detail, 2019, to which comparison with virtual reality is inevitable. This painting appears as a multicolored chessboard suggesting the enlarged pixelation of digital images, the atomic squares of contemporary figuration.

Working this way, the artist continues fathoming the reasons behind the construction of images, but above all, painting and its making. The making of the painting in this work is of utmost importance, because the many squares of different color are made by painting orthogonally overlapping strokes of color: first from top to bottom, then from right to left, and vice versa. This is a presentation of the virtuality of the digital, the absence of the body, with the slow and continuous presence of the repeated human gesture aimed at creating a real, physical painting made of many layers; a body-to-body with paint that thickens nearly to the point of sculpture.

Adopting this oppositional principle that creates works full of contradiction, and therefore productive contestation and controversy, "the overlapping warp and weft invites us to ask ourselves what we're looking at. Is this a two-dimensional or three-dimensional image? Is it an image that represents something or is it an abstract image? Is it technology or tradition, physicality or immateriality? (Parisi).

Some of these questions have been answered above, others might be answered below. We could start by saying that Parisi's mode of operation as artist follows the general principle of the modernist relation based—especially in architecture—on orthogonality, which we know not only as a practical means but, like perspective, a theoretical approach to knowing the world.

This theory and practice are also found in The Whole World in a Detail (fabric), 2019/2022, a blue, black and green triptych also made by pictorial layers whose chromatically sumptuous surface recalls the preciousness of the fabrics of clothes and curtains painted in Renaissance paintings. Here too, there is no figuration, but concentrating on a detail and exalting its chromatic aspect with diagonal spatula strokes reveals—we repeat— not a discourse on figuration or the representation it engenders but one centered on the analysis and presentation of painting, which is instead a strongly conceptual discourse. Let us not forget, then, that theories of modern abstract painting of the 20th century and the principle of hard and pure Cartesian orthogonality have been hotly debated, and that friendships have ended over it, such as the argument that arose between Mondrian and Van Doesburg when the latter introduced diagonals into De Stijl painting and Mondrian stopped speaking to him.

Fortunately, much water has passed under the bridge since then. Parisi can use diagonals, straight lines, curved lines, and so on indifferently today because his is not only modernism but also conceptualism, as well being as an active painting practice. Painting on fabric both during the Renaissance and after, precisely because of its qualities of precious luminosity and softness, was one of the most difficult exercises, as hard as capturing as capturing the complexion of people's bodies, and therefore also a method of evaluating both a painter's skill and cost. As a result, thought, technique, economy, and space converge in granting substance to the art in question, a very important operation represented by abstract forms that solicit our interpretive effort and demand non-passivity from the observer, who is asked to provide an opinion. Parisi, the first observer by absence of his works, is like the absent Lorenzo Lotto being watched by the young man he is portraying, or like what Giulio Paolini is focusing on in his Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto. Therefore, as I was saying, Parisi gives us works that amount to optical devices in similar fashion to the other work here on display, Unité d'habitation (2016) whose title clearly references the above-mentioned Le Corbusier and his utopia, which in addition to being a project people could live in, was a theory of seeing and color, which is a part of seeing, questions that were all discussed during modernism. Le Corbusier's Le Unité d’habitation are apartments built on two levels, dwellings from which no apartment can be seen from any other. This inability to visually share existence is the exact opposite of Jeremy Bentham's panopticon from where it was possible instead to take in everything from one point. Here, on the contrary, the gaze no longer takes in the public but is restricted to the private, while the public part is left in the open air of the terrace and therefore the collective space at the edge of the sky.

From indoors to outdoors, from space to color, also color assumes a public dimension in the hues of the facade and the private dimension of the colors inside the apartments. This is one of Le Corbusier's takes on painting, a painter himself and a believer in Purism hoping to further the Esprit Nouveau idea whereby this architecture, like Alberti's and Brunelleschi's, embraces not only the discipline of architecture but also painting.

The condition of seeing and concealing is explicated in the pictorial reasoning behind Parisi's works, such as in the 2016 painting mentioned above, Unité d'habitation, a work that plays on the very idea of seeing and concealing, just as Coast to coast (2007) plays on the idea of the art form. Here, layers of different color, oil beneath, acrylic on top, generate a living work that continues producing itself as the oil underneath slowly oozes out to create "spots" of different surfacing color and thus a continually different painting. This addresses the question of the open work in which meaning and form, authorship and co-authorship, are always in the process of becoming, never finished.

Eventually, however, and as mentioned above, territoriality, geography, space and other themes that the artist has addressed since he began painting also return in works such as Bench for Everybody, 2004, a work that can be put to use in the center of the room as a place to sit made in layers of cardboard whose orthogonality is interrupted by the shaping of the curved lines that adapt to the soft bodies of the people seated. Architecture becomes sculpture here in this encounter where the radical design for which Florence is famous meets modernism in the process of splitting evenly into post-modernism and neo-modernism.

This becoming sculpture from architecture evidently also appears in another of his works, the "architectural models" titled U.s.a.i.s.o., 2009>2013, an acronym for (One on top of the other clockwise) also made in layers of cardboard sheets with casts of the cardboard in plaster bespeaking the ancient process of infinite technical reproducibility. These are models that are not really models because they are intended as environmental sculptures, places where the various openings, the French windows and ceiling allude to the possibility of gazing outward: the landscape

These are sculptures and models that can also take on an environmental dimension, such as the one titled Observatorium at the Pecci Museum, 2004, in which the relationship with architecture, territory and space is emphasized further. Placed on the shelf before a gallery window, these model-sculptures are the first works to encounter the red light of glass tinted by a filter that diffuses different shades of red depending on the angle of the light coming in over the course of the day. This chromatic variation colors the entire room accordingly, changing from red to violet, the limits of the spectrum in which our eye is restricted.

Colors continue offering guidance and comparison in the second room, whose four walls are hung with four works, diptychs consisting of a photo and a painting. Here, the environment expands again with the sea of the Strait of Messina as its subject, hence, art made between and with Scylla and Charybdis; where, as mythology teaches, if you survive this context you can survive anything The works are exemplary, in fact, diptychs titled The Weather Was Mild on the Day of my Departure, 2018/2021, inspired by a chapter in Joshua Slocum's book, Sailing Alone Around the World, the tale of one person alone facing the landscape of the sea in which the comparison with the artist as a solitary being on the open sea of art is inevitable. The diptychs in question consist of one of the photos the artist took every time he travelled to Sicily by sea on the left and a monochrome painting on the right. The photos were selected from the countless shots Parisi took from the ferry as he crossed the Strait of Messina, photos of the mid-ground or mid-sea between two shores, between the peninsula and the island. This is diptych territory, for sure. The artist then selected the most appropriate photo to juxtapose his monochrome paintings with no apparent connection but with color chosen because of some reference or relationship found in the photo or some detail present in each one. They construct both Paolo Parisi's point of view and our own.

Giacinto Di Pietrantonio