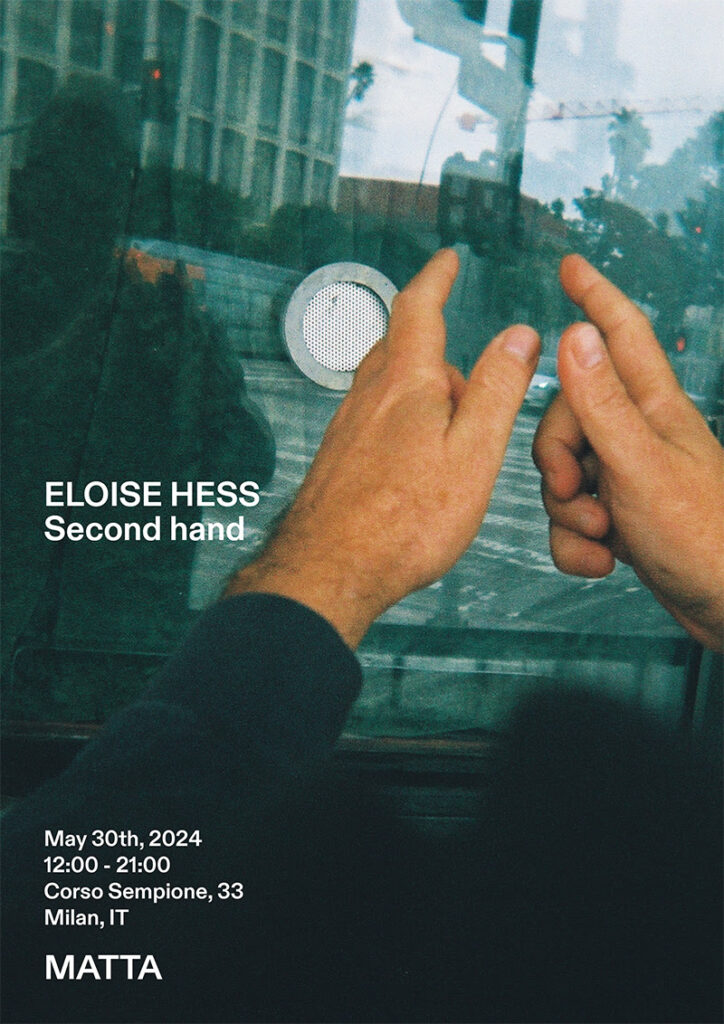

SECOND HAND

Text by Jennifer Pranolo

“...the picture is first felt by us...”

–Jacques Lacan, “What is a Picture?”

Within the series, a gesture repeats. Each time it appears, it is not the same. Yet also

each time, it is of hands reaching. They overlap, once, almost into a prayer; in others,

they grasp, unevenly, for something that is not there. Reaching repeatedly, the hands

frame an intention: a desire to see.

*

The photographs are taken on a disposable camera. The ease of the single-use, point-

and-shoot facilitates the promise of photography: an instantaneous mastery of space

and time in the making of a record, on sight, of light writing itself into memory. An

instrument of capture, the camera is a dark room for this precise aim of seizing the

present as it passes, a seeing that can be held and seen again.

*

But it is a painting that holds the photograph—or photographs, twelve selected from

nearly five hundred—of the missed aim to make a picture out of what is seen. The artist

Eloise Hess (b. 1995) collaborated with her father Charles Hess (b. 1961) to register the

slow-motion atrophying of the linkages between the hand, mind, and eye; the lapses, an

accumulating discontinuity, between his actions and his intention. One gesture replaces,

or imperceptibly iterates, the other; one way of seeing, through one medium, falters,

while attended to, in another medium, by a different way. In the lag, the image forms.

*

Paintings are not photographs. The latter historically supersede the purpose of the

former as imitations, or representations, of reality. Like modern acheiropoieta, icons that

are not made by hand, mere presence leaves a mark, verifying contact with the

insubstantial. The photographic impulse to fix this circuit of truth and touch into a picture

of, a clear likeness or impression, devolves, in Hess’s paintings, into an intensive blur.

Translucent shadows, edges, and occlusions arise as the camera slips, descends, turns

inward, away. Dim gradations serially displace sight.

*

A sense of passage permeates these paintings—but how? Moving neither forward nor

backward, the image is extracted from its photographic substrate and reassembled on

multiple sheaths of silkscreen and inkjet prints or transfers bound by alternating layers

of encaustic in a vertical still of stacked process. Where the successive frames of a

projected filmstrip can create the illusion of cinematic continuity aided by the fallibility,

the slowness, of the human eye—here, the desire of painting, its unfolding of a gesture,

of many, and more, gestures, interrupts the photograph’s single plane. Time, gesture,

and desire indivisibly expand a singular instant.

*

The medium of desire is time. Desire never attains its aim, just as the second hand on

an analog clock keeps time at a distance by elongating, indefinitely, the space between

the minutes and hours that divide a day, or a life. Vision, alongside desire, persists in

afterimages. Hess photographs her father—a photographer experiencing the

incremental forgetting associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease—trying to see as

his capacity to picture the world, to remember and put it in order, fades. The obscure or

not taken shots that her paintings discretely develop do not offer a revelation but instead

point to a shared time. A desire to touch time’s movements through sight opens the

orientation of the picture, and the relation, to change.

*

The poet Arkadii Dragomoshchenko begins his book Xenia with a scene of reversible

reciprocity that turns on seeing oneself being seen, wanting, oneself, to see: “We see

only what / we see // only what / lets us be ourselves— / seen.” It is a seeing that one

feels.

_______________________________________ |