My soul is wrought to sing of forms transformed to bodies new and strange!

Ovid, Metamorphoses.

Research reveals that the oceanic crusts are much simpler and younger than the continental crusts with some 100 million years separating the oldest oceanic rock from the oldest continental one. The ocean floor is young because it is constantly destroyed and renewed. Similarly, the southern and eastern coastline of the British Isles with their sweeping lines are younger meetings of sea and land, whilst the northern and western coasts - characterised by embattled bays and headlands - are the more ancient shores. Though impressed on the mind and the map as a clear and delineated boundary, the shoreline itself is in motion, impacted by the sea and other forces, both natural and manmade.

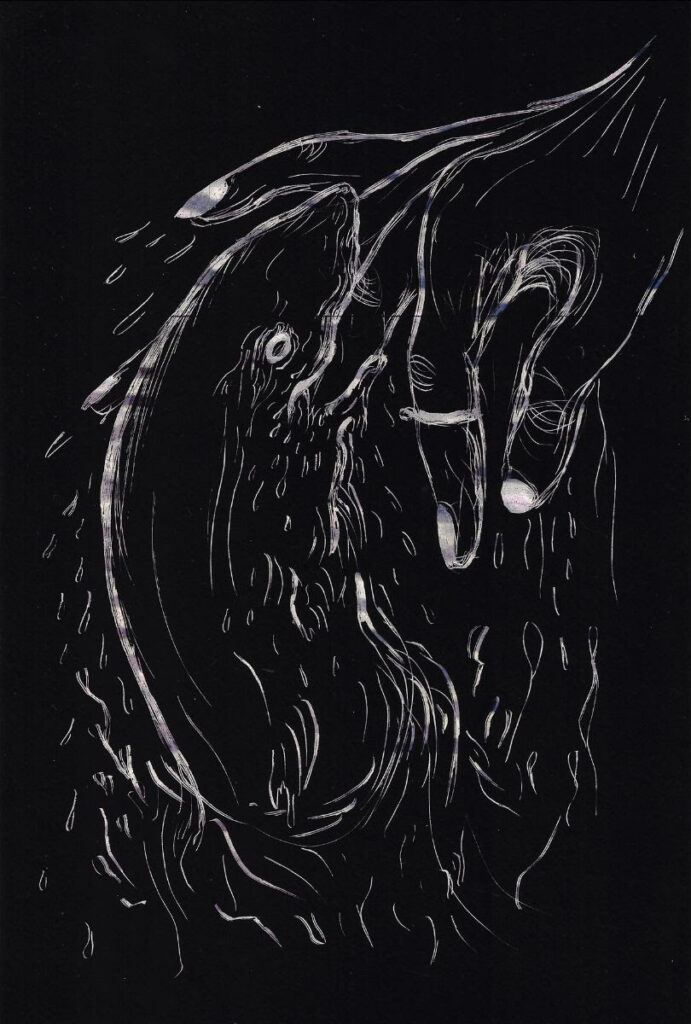

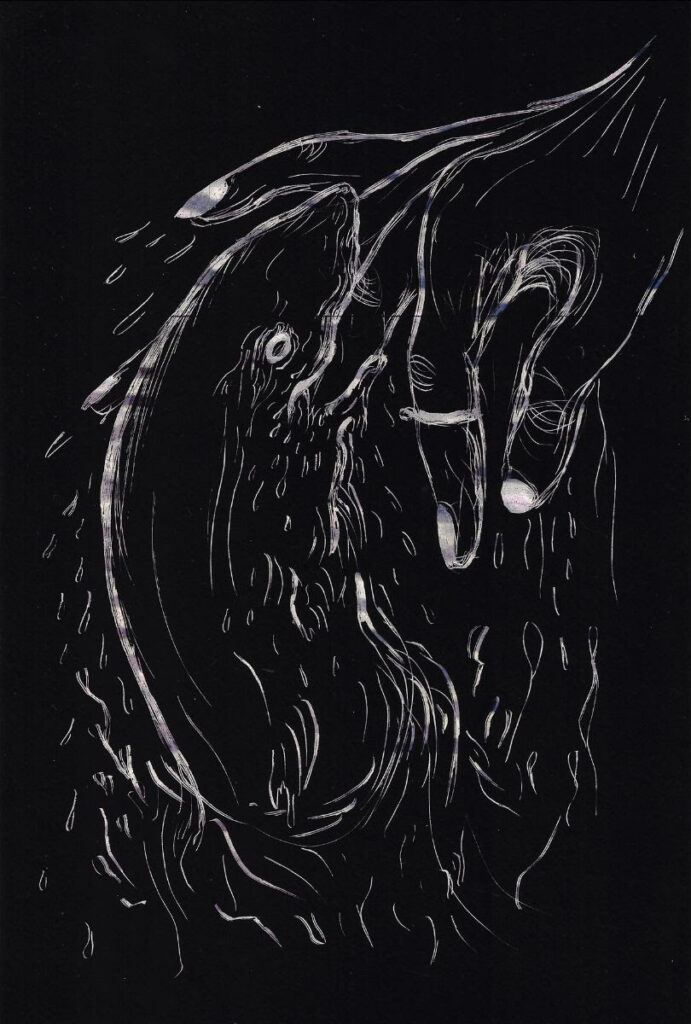

Zoe William’s film Tendresse, Tendril, (Worms’ Meat) (2021) was made in Cornwall, on and around that ancient western coastline of England. The film is concerned with the liminal spaces of shorelines and rock pools as birthing places for life as well as sites of danger and death. During the making of the film, Williams was researching the work of the Cornish artist Ithell Colquhoun, using her interest in Occultism, Surrealism and the erotic to draw out the histories of magic and new age practices that characterise the distinctive culture of the Cornish peninsula. Tendresse, Tendril, (Worms’Meat) shares Colquhoun’s interest in constructing rhythmic sequences from natural forms and dismembered quotidian objects to produce ritualistic significance. However, William’s work departs from Colquhoun’s through her interest in more indecorous forms. Williams deploys the grotesque, camp, and absurd humour to explore the ways in which the profane human system of exchange has taken on a mythical quality in our world. Like the Italian artist Carol Rama, she explores the symbolic potency of female sexuality and its inseparability from aggression, even violence. This violence in Rama’s work as in Williams’ is mediated through a series of bawdy, irreverent symbolic fragments. Tongues, shoes, turds and foxes for Rama; fingers, oysters, vulvas and eels for Williams.

Williams’ returns regularly in the film to the sea-anemones she encountered in the sea around Cornwall. Known as ‘Snakelocks’, these soft, tentacle-like forms are resplendent in putrid greens and purples. The way the Snakelocks move in the water draws you toward them, imagining a soft, undulating touch. Yet in reality, the tentacles are poisonous and give a nasty sting. The ‘Snakelock’ motif draws on Williams’ interest in the snake-haired gorgon Medusa, the head of which Perseus used to turn the sea monster Cetus to stone, and the Algol star, which is said to represent Medusa’s blinking eye in the cosmos. Algol’s name is derived from the Arabic Al Ghoul, meaning “demon,” “evil spirit,” or “devil.” The word is derived from the same semantic root as “alcohol.” Williams plays with intoxication in the work: the acts of looking, touching and digesting are muddled by jouissance. Feminine erotic impulses unsettle the notion of a nurturing mother nature in Tendresse, Tendril, (Worms’Meat), driving toward consumption and death as central yet unpredictable forces in a doomed libidinal quest for lost plenitude.

Ancient stargazers were unnerved by Algol because of its rhythmic changes in brightness. The ancients considered Algol to represent misfortune, an interpretation still prevalent in modern western astrology. The epic poet Homer wrote of Algol in the Iliad: “...the Gorgon’s head, a ghastly sight, deformed and dreadful, and a sight of woe.” Williams' work recuperates the dreadful fragments of mythic and real bodies through the distinctive modernity of camp, embracing the unnatural, the artificial and the exaggerated to create new significance. By doing this, Williams offers us a playful, private vision animated by the transformation of the world around her through imagination. We see shards of nature and culture, of sexuality, of love and pain, registered, dissolved, and internally reconstituted in such a way as to give them idiosyncratic meanings. Through her work we glimpse our own inner lives, organised as they are through symbols and narratives that were once part of a previously existing whole.

- Freya Field-Donovan