Demolizioni. In India tocca a un capolavoro di Louis I. Kahn

Giovanni Leone, architetto e profondo conoscitore della realtà indiana, racconta la vicenda piuttosto assurda che sta in questi giorni svolgendosi in India: demolire un capolavoro di Louis I. Kahn. Il problema non è tanto la demolizione in sé, ma un'idea nazionalista di cosa preservare e cosa invece buttare giù.

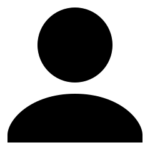

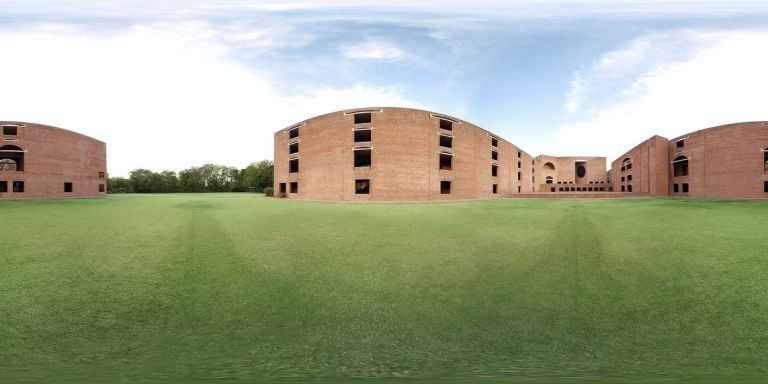

Una (cattiva) notizia è giunta insieme a Gesù bambino alla Vigilia di Natale, proveniente da Oriente come i Re Magi ma senza portare doni: la direzione dell’Indian Institute of Management di Ahmedabad (IIMA) comunica con una lettera all’associazione Alumni del prestigioso istituto per la formazione di manager la decisione di demolire la maggior parte dei dormitori del campus progettato da tra il 1962 e il 1974 da Louis I. Kahn, uno dei più grandi maestri dell’architettura novecentesca.

In un battibaleno la notizia fa il giro del mondo dell’arte e dell’architettura, provocando unanime indignazione e sfociando in un appello alla mobilitazione in difesa di questo capolavoro dell’architettura. Difficile sottrarvisi, nonostante si tratti dell’annuncio di una decisione presa e non di un’ipotesi: non si combatte per vincere, ma perché è giusto farlo. Nella comunità locale il dibattito è stato subito acceso, e non solo tra gli architetti. Ad amplificarlo è venuto il diluvio di mail e messaggi che si è abbattuto su Ahmedabad dal mondo intero. Si sono moltiplicati gli appelli alla direzione dell’Istituto, hanno scritto i figli di Kahn, esponenti della comunità accademica e una lettera, grazie alle nuove tecnologie, è stata sottoscritta allo stesso tempo da architetti e professori e studenti di tutto il mondo. Il nuovo anno ha portato poi la (buona) notizia d’interrompere l’iter per l’imminente demolizione, solo la sospensione della decisione e non ancora la rinuncia, ma è già un successo e potrebbe non essere il solo motivo di soddisfazione.

ARCHITETTURA E SOCIETÀ

Qualunque sia l’esito della vicenda, un risultato che si è ottenuto è stata di riflettere sull’architettura e i suoi fondamenti sociali, rendendo accessibile anche insieme a chi architetto non è una disciplina incompresa ai più. Alle basi dell’educazione e della formazione ci sono lettere e numeri, ma non s’insegna ad alzare lo sguardo e a comprendere il senso di segni e forme. L’architettura è spesso considerata disciplina indisciplinata ai limiti dell’arbitrio, trascurando che il suo fondamento è sociale e relazionale, la sua natura “bastarda”, fluttuante tra le istanze dei suoi fronti umanistico (con i suoi aspetti poetici fondati sul bello che sono estetici ma anche letterari del testo architettonico) e scientifico (del rigore di calcolo e tecnica e materiali e funzionalità) alla ricerca di equilibrio tra il bello e il buono.

I puri tecnici la considerano poco rigorosa, i letterati non ne apprezzano la poetica, gli artisti la ritengono troppo tecnica. Occasioni come questa vanno colte al volo per spiegarsi e spiegare. La decisione di demolire un’architettura non deve scandalizzare a priori, non è inconcepibile e anzi può far parte del naturale corso degli eventi. Ogni cosa ha un suo tempo, anche l’architettura, che prima o poi finisce, anche se si tratta di un capolavoro. In quel caso è doveroso interrogarsi e capire il perché di questa scelta e, quando non risulta chiaro, occorre approfondire, indagare, perché c’è sempre una ragione e quella più evidente è spesso solo apparente. Nel caso in cui non si trovi una buona ragione, non resta che combattere. Non è da escludersi che dietro alle quinte di questa decisione possano esserci le ambizioni di qualcuno che voglia acquistare evidenza, anche scandalizzando.

IL RESTAURO DELL’IIMA NEGLI ANNI SCORSI

Nella lettera del Prof. Errol D’Souza, direttore dell’IIMA, si legge che pesano sulla decisione gli impegnativi interventi di restauro a cui è necessario sottoporre gli edifici, ma specialmente si ventila un rischio per la pubblica incolumità a causa dei rischi di crollo in caso di terremoto. Queste motivazioni sono ragionevoli ma non convincono tecnici e specialisti, perché sono e resteranno generiche finché non saranno supportate da dati, rapporti, relazioni, perizie che ad oggi non sono stati resi pubblici. Le informazioni reperibili vanno infatti in direzione opposta alla decisione assunta.

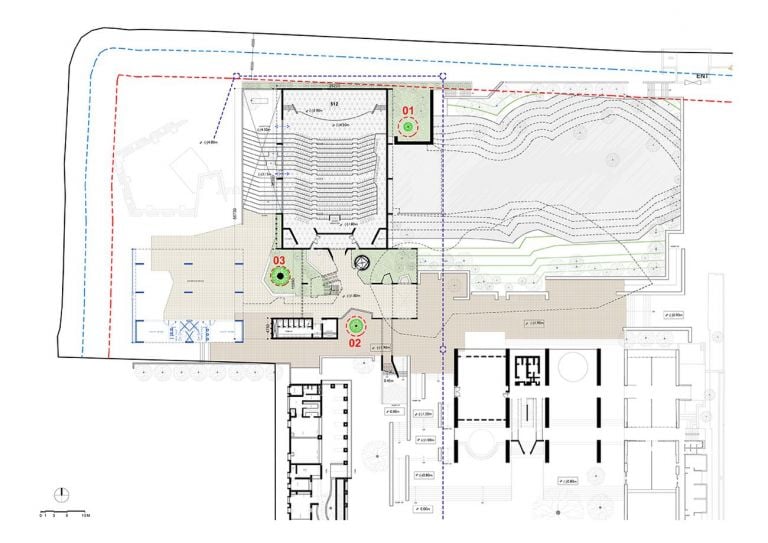

Nel 2014 è stato bandito un concorso per il restauro del campus, aggiudicato dalla società Somaya & Kalappa di Mumbai, altamente qualificata, che opera nel campo del restauro fin dalla sua fondazione nel 1975. Completata la fase di analisi e rilievi (2014-15) si è proceduto a un intervento campione di recupero del dormitorio D15 (2015-17) insieme al restauro del corpo della biblioteca (2016-18) e a quello della facoltà, avviato nel 2019 e attualmente in corso. In una conferenza del 28 novembre scorso – quindi neanche un mese prima dell’annuncio dell’intenzione di demolire – l’architetto Brinda Somaya illustra i lavori di recupero in corso di realizzazione sul complesso architettonico, un intervento esemplare per il rispetto che merita un’architettura come questa e per il rigore delle analisi e delle indagini preliminari che hanno orientato il progetto di ristrutturazione documentato nella conferenza.

Nulla lascia qui presagire l’imminente decisione, i progettisti ne erano ignari, dato che Somaya racconta che, per consentire la prosecuzione dei lavori negli altri dormitori, si prevede di spostare gli studenti in edifici collocati nel campus realizzato in un’area contigua. Il campus necessitava obiettivamente d’interventi, non solo per i danni provocati dal violento terremoto del gennaio 2001, ma specialmente per i problemi derivanti da “peccati originari” come: l’utilizzo di mattoni di scarsa qualità che ha dato problemi all’intera muratura fino alle fondazioni; la sperimentazione di una soluzione per dare maggiore solidità alle murature rivelatasi estremamente dannosa, effettuata inserendo dei tondini a grande aderenza in ferro in fori verticali privi di adeguata sigillatura, il che ha provocato con l’ossidazione lo sfogliamento del mattone. Tutto ciò non è però determinante. Lo dimostrano centri storici come Venezia, una città interamente costruita in legno e mattoni, materie di cui si conoscono i difetti e il grande pregio di potersi rinnovare progressivamente per parti: anche se non è lì consentita la demolizione e ricostruzione, la città continua a offrirsi allo stupore del visitatore.

ENTRA IN SCENA BIMAL PATEL

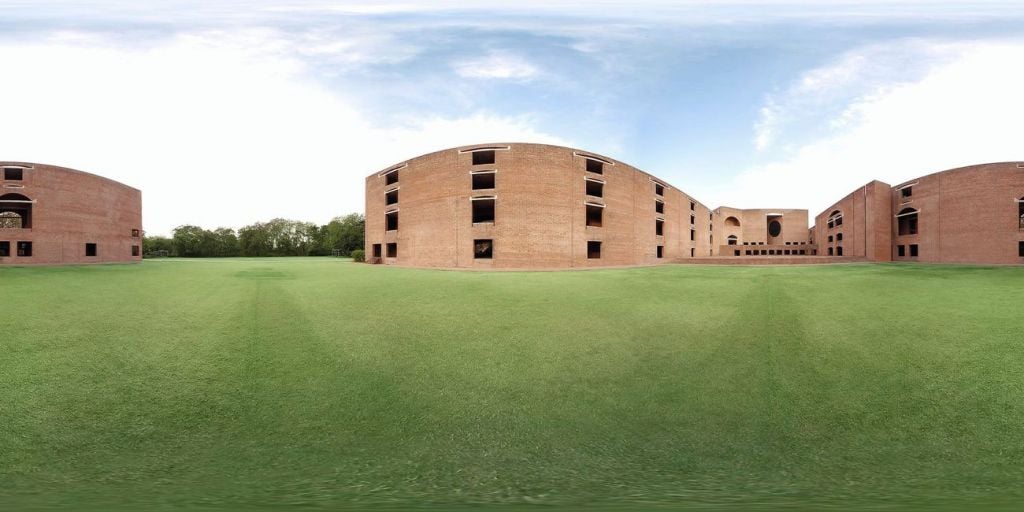

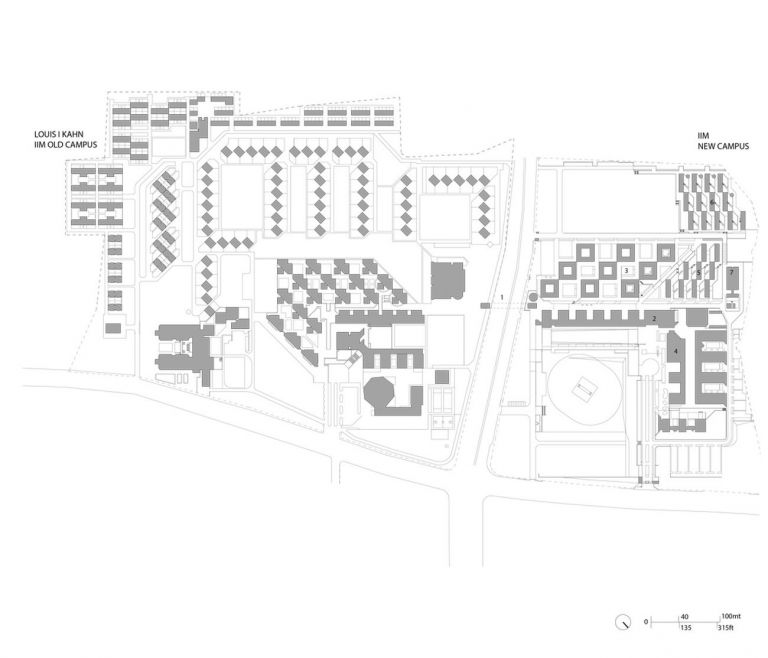

Ci sono degli altri elementi di cui tenere conto. Tra il 2001 e il 2009 al campus si aggiunge la costruzione di un secondo campus come sua estensione, in un’area contigua, separata da una strada che viene scavalcata dal progetto per collegare le due aree.

Il progetto è redatto dall’architetto Bimal Patel, figlio d’arte e astro nascente del panorama architettonico cittadino. Insieme a questa informazione già nota, se ne apprende una dalle colonne del quotidiano Times of India del 4 gennaio 2021, in cui si legge che già un paio di anni fa è stato conferito incarico alla società di progettazione ARCOP Associates Private Ltd per la ricostruzione degli edifici di Kahn che s’intende demolire, quindi la decisione appare già consolidata ben prima della lettera di Natale. Inoltre, tale incarico è conferito sulla base di un Master Plan del 2014 redatto nuovamente dall’architetto Bimal Patel, come si vede nel sito della HCP.

Non è questa la sede per approfondire i dettagli tecnici, ma prima di procedere oltre con la decisione di demolire i dormitori dell’IIM dovrà essere valutato il rapporto costi/benefici di tutte le opzioni possibili, dal restauro alla ristrutturazione e fino alla demolizione e ricostruzione che in certi casi, come quello veneziano, aiuta a intervenire celermente senza perdersi in estenuanti dibattiti. Si troverà certamente qualcuno che possa sostenere l’inevitabilità della demolizione ma bisogna dare il diritto alla comunità locale e a quella internazionale dell’architettura e dell’arte di vagliare e confutare le tesi che verranno proposte.

Christopher Charles Benninger, CEPT, Ahmedabad. Intervento sul progetto di B. V. Doshi

ALTRI ARCHITETTI VITTIME AD AHMEDABAD

Il caso dell’IIMA non è un caso isolato ad Ahmedabad, ci sono vari precedenti e – se non si provvederà ad arginare la tendenza – ci sono seri rischi per il futuro, potrebbero risultare a rischio altri capolavori come la Villa Shodhan di Le Corbusier alla luce dell’incremento delle quotazioni fondiarie che ha fatto lievitare il valore della sua area di pertinenza. Oggi la proprietà tutela il bene di cui si prende cura con rispetto e attenzione, ma potrebbe in qualunque momento cedere alla tentazione di procedere a uno sviluppo della densità con demolizione e ricostruzione con incremento volumetria per ottenere lauti guadagni. Nessun vincolo grava infatti su quella straordinaria architettura. È inconcepibile che ancora ci siano luoghi che ospitano beni di importanza tale da travalicare i confini locali e nazionali, privi di strumenti di tutela e garanzia, il mondo della cultura e le comunità locali devono pretendere che i governi nazionali e le istituzioni internazionali adottino opportuni strumenti normativi, prima che sia troppo tardi e i danni irreversibili.

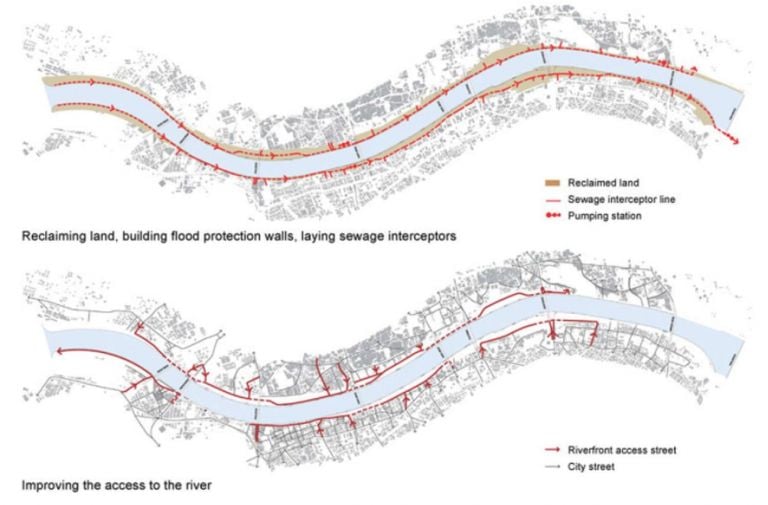

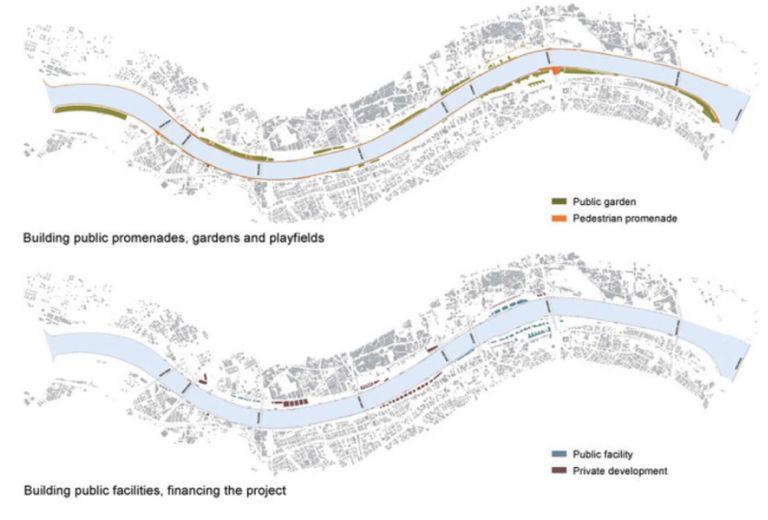

Un precedente già realizzato è il rifacimento del riverfront, la riduzione dell’alveo del fiume che attraversa la città, il Sabarmati. L’intervento era stato proposto ancora nel 1960 con l’intento di riqualificare il fiume (inquinato da scarichi fognari privi di impianti di depurazione) e le rive (in stato di abbandono e su cui si erano insediati vasti slum). Venne poi modificato a più riprese, incrementando progressivamente la volumetria delle aree edificabili, giustificata dalla necessità di finanziare l’intervento. Si è così di fatto affermata una discutibile idea di sviluppo che assume i caratteri della speculazione fondiaria, tanto da generare dal nulla nuove aree edificabili senza tenere nel dovuto conto le istanze ambientali e paesaggistiche. Il risultato è stata la trasformazione del fiume in un canale con larghezza costante di 263 metri e rive rettilinee in cemento armato. La necessità di impedire l’erosione, controllare i flussi d’acqua, allocare la rete fognaria, non giustifica la cementificazione delle rive e l’assenza di qualsivoglia intervento di naturalizzazione. La sistemazione si distingue per il suo anacronismo, avrebbe potuto essere l’occasione per realizzare un intervento di stampo ambientale ed ecologico a interessare il corso del fiume anche extraurbano, invece… Un’indicazione opposta veniva da un altro capolavoro d’avanguardia ancora di Le Corbusier, il Palazzo dei Filatori, che presentava un dispositivo bioclimatico di facciata raffinato e di grande efficacia con un frangisole grande come l’intero prospetto, a proteggere l’edificio dall’insolazione agevolando l’ingresso delle brezze raffrescate dall’acqua del fiume sul quale si affacciava, che poi attraversavano l’edificio raffrescandolo. Anche in questo caso è stato provocato un danno all’opera, che ha perso il rapporto con l’acqua, portata a distanza sottraendo uno dei fattori qualificanti. Fortemente voluta da Narendra Modi, allora Presidente dello Stato del Gujarat e oggi Primo Ministro indiano, la progettazione del riverfront viene aggiudicata nel 2005 alla HCP Design, Planning and Management Pvt. Ltd., società di progettazione che fa capo a Bimal Patel, e viene inaugurato il 15 agosto 2012, Independence Day indiano.

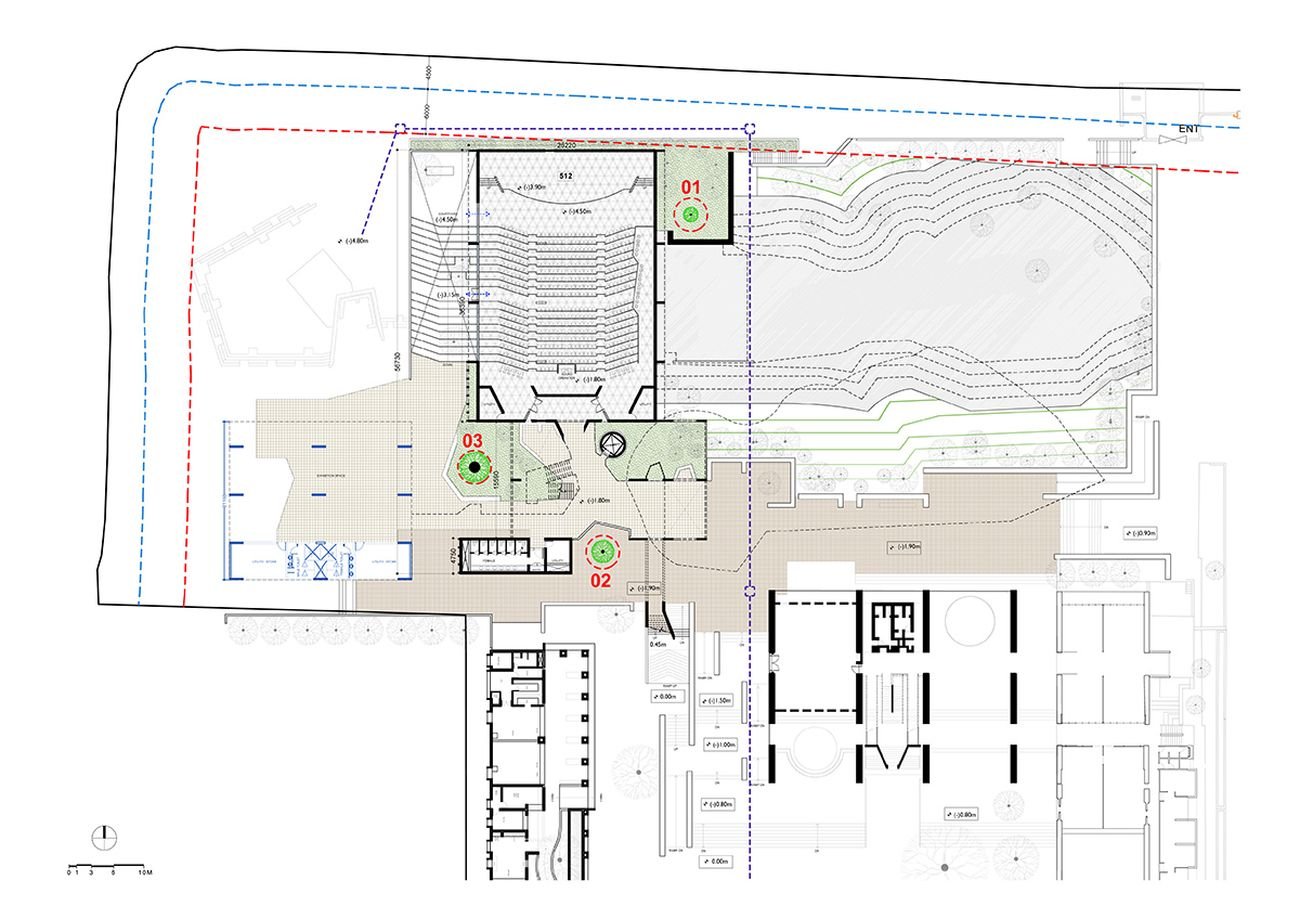

Altro caso controverso è stata nel 2015 la modifica della sede del CEPT, la scuola di architettura e pianificazione fondata da B. V. Doshi, che è un gigante della storia contemporanea, unanimemente riconosciuto come maestro di architettura e di vita. Avendo la fortuna di avere l’autore in buona salute e ancora in attività nella medesima città, si sarebbe dovuto almeno consultarlo prima di accostare nuovi fabbricati a quelli esistenti, modificando gli spazi che erano parte integrante e significativa dal progetto originario. Una mancanza di rispetto che si sarebbe potuta evitare. All’opera di Doshi sarebbe auspicabile riconoscere il diritto d’autore apponendo i vincoli conseguenti, com’è stato il caso del condominio Cicogna alle Zattere di Gardella, a cui viene apposto nel 1995 (con l’autore in vita) il vincolo di “protezione del diritto d’autore”.

La gigantesca statua di Vallabhbhai Patel sul fiume Narmada

UNA ARCHITETTURA NAZIONALISTA

In ogni epoca c’è stato un architetto disposto a tutto pur di vedere realizzata la propria visione. Nel 2015, in occasione di una mostra al Beaubourg su Le Corbusier, si apre un dibattito sul rapporto tra architetti e potere ripresa tra l’altro sulle colonne de L’Espresso. Lanciato da L’Obs e da Le Monde, nei media e tra gli intellettuali si è acceso un dibattito che tocca due nervi scoperti. Uno riguarda l’elaborazione culturale della Francia filofascista e filonazista, capitolo a tutt’oggi – spiace dirlo – minimizzato. E uno il mondo degli architetti, per il loro rapporto ambiguo con i regimi. Quello che ha spinto tanti nomi illustri del moderno a corteggiare Stati autoritari e dittature: da Le Corbusier a Piacentini, dagli Speer padre e figlio a Boris Iofan a Philip Johnson, su su fino a oggi, ai Norman Foster e ai Rem Koolhaas che fanno affari con emiri arabi, oligarchi russi, il partito-Stato cinese. Deyan Sudjic, direttore del Design Museum di Londra, la chiama “disponibilità a stringere accordi di tipo faustiano” con il regime al potere, “qualunque esso sia”.

Dal 2013 Presidente e Direttore Esecutivo del CEPT, Bimal Patel è l’autore del lungofiume e si distingue per la capacità di dar forma ai sogni di Narendra Modi, a partire dal complesso per uffici pubblici intorno al palazzo dell’assemblea dello Stato del Gujarat a Gandhinagar. Le sue capacità sono confermate dalla ricezione nel 2019 del Padma Shri Award, dopo il quale sono arrivati gli incarichi per lo sviluppo del lungomare di Mumbai, il Kashi Vishwanath corridor a Varanasi, il faraonico progetto per il cuore della capitale indiana di cui diremo più avanti.

Al Primo Ministro e leader del Bharatiya Janata Party (il BJP, fondato nel 1980, è il maggior partito conservatore del Paese, fautore di una politica estera nazionalista e di difesa dell’identità induista, che ha intenzione di ridurre l’autonomia concessa a Stati di frontiera con il Pakistan come il Jammu e Kashmir) vengono contestate megalomania, ostentazione di vanità e manie di grandezza per le grandi opere di cui si fa promotore, come:

- la costruzione del tempio Ram Mandir a Ayodhya, città sacra all’induismo, legata all’eroe rama del poema epico Ramayana dal costo di 123 milioni di euro, inaugurato il 5 agosto 2020;

- la costruzione del Gandhi Mandir a Gandhinagar, capitale del Gujarat, con museo e centro congressi. L’edificio del “mausoleo” si presenta con la forma degli accumuli di sale ingrandito fino alla grandiosità delle piramidi egiziane;

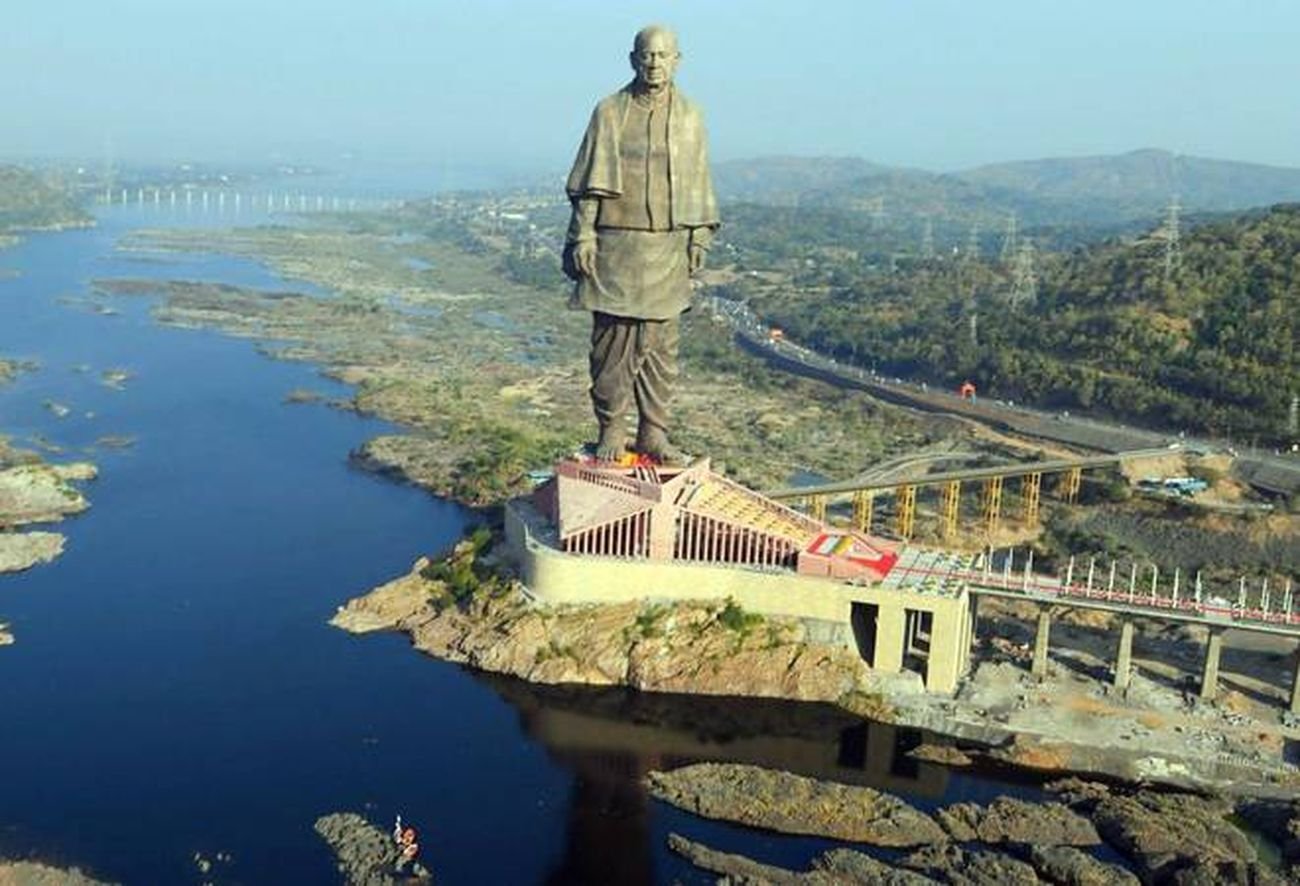

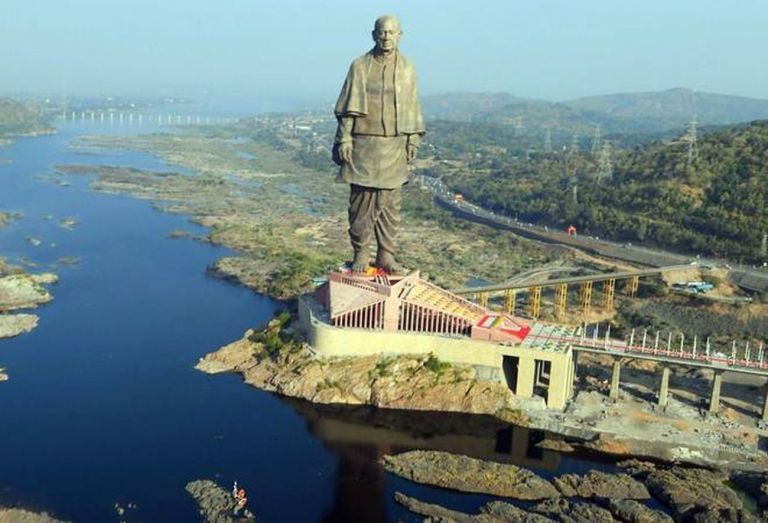

- la costruzione vicino alla grande diga sul fiume Narmada della statua più grande del mondo (il doppio della Statua della Libertà), dedicata a Vallabhbhai Patel, esponente conservatore di spicco dell’indipendentismo indiano prima e del Partito del Congresso poi, come Gandhi era avvocato e nativo del Gujarat, e come lui torna a vivere ad Ahmedabad dopo aver esercitato in Gran Bretagna. È denominata la Statua dell’Unione. Nel 1947 Patel fece ostruzionismo nella spartizione dei beni mobili fra India e Pakistan e questa fu una delle cause della vulnerabilità militare del Pakistan in quegli anni, posizione in parte ammorbidita in seguito all’ultimo digiuno di Gandhi nel gennaio1948.

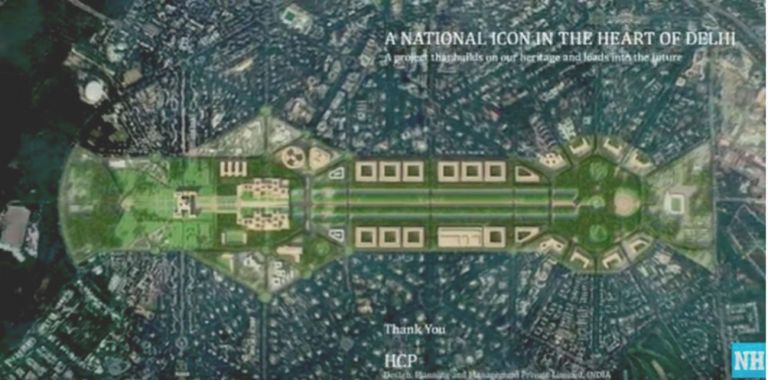

- il ridisegno del cuore della capitale. Il progetto per il Redevelopment of Central Vista Common Central Secretariat and Parliament di Delhi, l’asse del Central Vista e il parlamento verranno completati per il 2022, mentre il complesso del Palazzo del Governo nel 2024.

Quella in atto sembra una battaglia conservatrice e iconoclasta, che non si limita a rileggere selettivamente la Storia ma vuole correggerla in una prospettiva nazionalista, sovrascrivendo le tracce delle sistemazioni culturalmente “straniere”. Una radicale inversione di tendenza rispetto a quello seguito all’Indipendenza, che era un approccio di positiva apertura alla cultura internazionale più avanzata, senza pregiudizi di carattere geografico o culturale.

Gandhi Mandir, Gandhinagar. Photo Gianni Leone

LIVING ARCHITECTURE

L’architettura vivente è quella vissuta, non teoria ma pratica partecipata di natura sociale, azione positiva d’innesco di un processo che ne è il prodotto. Il processo è quello della trasformazione e dell’adattamento dello spazio in funzione dell’abitare, un esercizio che riguarda la dimensione fisica e spirituale. Lo spazio che ne deriva influenza e condiziona a sua volta chi lo indossa, nel bene e nel male: può provocare ben-essere (che non è il comfort) o disagio, come quello che si prova indossando l’abito di qualcun altro, che sentiamo non appartenerci perché ci sta troppo stretto, una giacca con le maniche corte o dei pantaloni lunghi oltre misura. Ecco, l’architettura deve avere il senso della misura, non è sfoggio di abilità e virtuosismi ma umile capacità d’interpretare lo spirito del tempo, dei luoghi e dell’abitante che deve vestire l’abito. In questo senso l’architettura è un taglio sartoriale cucito su misura addosso al corpo sociale, e deve calzare come una pelle che cambia che cambia insieme a noi. Raggiungere l’obiettivo una volta per tutte è impossibile, s’intende e si tende a far coincidere l’abito e il monaco con l’approssimazione caratteristica dell’intenzione e della tensione. Il risultato? L’habitat, teatro delle interazioni tra forme viventi, complesso e contraddittorio come il mistero della vita. Lo spazio che ci circonda è lo specchio della comunità che lo abita, un testo significativo che noi tutti scriviamo e riscriviamo quotidianamente aggiungendo espressioni felici o infelici, urlate o appena sussurrate tra le righe di pagine dense di errori, cancellature, pagine strappate. Anche senza insegnare a leggerlo, s’impara a conoscerlo e ad apprezzarlo, natural-mente.

È questo il caso. La decisione di intervenire al CEPT ha provocato nel 2015 corpose proteste da parte degli studenti di oggi e degli allievi di ieri, numerosi al punto da rappresentare diverse generazioni. Diverso è il caso dell’Indian Institute of Management. In entrambi i casi, chi ha preso posizione e ha chiesto di essere ascoltato sono stati gli utenti, la comunità di professori, studenti e ricercatori, raccolti nell’associazione Alumni, ma nel secondo caso si tratta di specialisti dell’economia e non dell’architettura. Al di là dell’esito della vicenda, sarà fonte di soddisfazione per Doshi, che oltre all’IIMA ha progettato l’IIMB, con sede a Bangalore. In entrambi i campus la natura s’insinua fin quasi dentro le aule, intenzionalmente, per far presente a chi dovrà occuparsi di economia che la matematica ha i tratti del divino e non solo quelli del profitto.

Così era anche al CEPT, con la modulazione ondulata del suolo fuori dal corpo delle aule dove gli studenti potevano sdraiarsi, facendo esperienza di uno spazio di complicità tra natura e artificio. Oggi è stata sostituita da una sistemazione estetica con un progetto dell’architetto Christopher Charles Benninger, che ha rimosso la componente etica di spazi poetici di servizio alla formazione degli architetti ridotti a meri spazi funzionali.

Le mobilitazioni confermano che il messaggio di quelle architetture è arrivato a destinazione, la consapevolezza che sopra-tutto la Natura è stata involontariamente metabolizzata, bīja il seme è a dimora e la fertilità dei suoi frutti contrasterà l’aridità dell’ignoranza. L’interrogazione e il dubbio sono il sale del sapere e dei processi educativi, che non sono esclusiva di accademici o uomini di potere, il sapere non risiede in un’aula ma scorre nell’esempio, la più alta forma d’insegnamento. Grazie dunque a queste comunità per essersi fatte coscienza critica. Speriamo si riesca a scongiurare il rischio di una dissennata demolizione, in ogni caso quella in atto è una battaglia culturale che val la pena di combattere per costruire ponti non muri.

– Giovanni Leone

ACQUISTA QUI gli scritti di Louis I. Kahn

ACQUISTA QUI il catalogo della mostra di Doshi al Vitra Desigm Museum

ENGLISH VERSION

The demolition of the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, a masterpiece of Modern Architecture by Louis I. Kahn, has been announced

The idea comes from a (bad) news that came together with the newborn Jesus on Christmas Eve, coming from the East like the Magi but without bringing gifts: the direction of the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (IIMA) communicates with a letter to the Alumni association of the prestigious institute for managers, the decision to demolish most of the dormitories on the campus designed from 1962 and 1974 by Louis I. Kahn, one of the greatest masters of twentieth-century architecture. In a flash, it went around the world of art and architecture causing unanimous indignation and resulting in an appeal to mobilize in defence of this masterpiece of architecture. Difficult to escape from it, even if it is the announcement of a decision made and not a hypothesis: we do not have to fight to win, but because it is right to do it when is the case and this it is. In the local community, the debate was immediately heated and not only among architects. The deluge of emails amplified it. and messages that hit Ahmedabad from all over the world. Appeals to the direction of the Institute have multiplied, wrote Kahn’s children, exponents of the academic community and a letter, thanks to new technologies, was signed at the same time by architects and professors and students from all over the world. The new year then brought the (good) news of interrupting the process for the imminent demolition, only the suspension of the decision and not yet the renunciation but it is already a success and may not be the only reason for satisfaction. Whatever the outcome of the story, a result that was achieved it has been to reflect on architecture and its social foundations, making the accessible also to who is not an architect a misunderstood discipline to most. Indeed at the basis of education and formation, there are letters and numbers, but it is not taught to look up and understand the meaning of signs and forms. Architecture is often considered an undisciplined discipline to the limits of arbitrariness, neglecting that its foundation is social and relational, its “bastard” nature, floating between the instances of its humanistic fronts (with its poetic aspects based on the beauty that is aesthetic but also literary of the architectural text) and scientific (of the rigour of calculation and technique and materials and functionality) in search of a balance between the beauty and the good.

The pure technicians consider it not enough rigorous; the writers do not appreciate its poetics; the artists consider it too technical. Opportunities like this must be taken to get over it and to explain. The decision to demolish an architecture should not be a priori scandalous, it is not inconceivable and indeed it can be part of the natural course of events. Everything has its own time, even architecture, which sooner or later ends even if it is a masterpiece. In that case it is necessary to question and understand the reason for this choice and if it is not clear, it is necessary to deepen, investigate, because there is always a reason and the most obvious one is often only apparent. If a good reason is not found, all that remains to do is to fight. It cannot be excluded that behind the scenes of this decision there may be the ambitions of someone who wants to acquire evidence, even scandalizing.

In the letter from Prof. Errol D’Souza, director of the IIMA, we read that the important restoration interventions to which the buildings must be subjected weigh on the decision, but especially it matters a risk to public safety due to the danger of collapse in case of an earthquake. These reasons are reasonable but do not convince technicians and specialists because they are and will remain generic until they are supported by data, reports, reports, appraisals that have not been made public yet. The information available goes in the opposite direction to the decision taken. In 2014 the IIM has launched a competition for the restoration of the campus awarded to the highly qualified company Somaya & Kalappa of Mumbai, which has been operating in the field of restoration since its foundation in 1975. After the analysis and surveys phase was completed (2014- 15) a sample recovery intervention was carried out on dormitory D15 (2015-17) together with the restoration of the library body (2016-18) and that of the faculty started in 2019 and currently in progress. In a lecture on 28 November – not even a month before the announcement of the intention to demolish – the architect Brinda Somaya illustrates the restoration work underway on the architectural complex, an exemplary intervention for the respect that architecture like this deserves and for the rigour of the analyzes and preliminary investigations that guided the renovation project documented in the conference. Nothing here suggests the imminent decision, the designers were unaware of it given that Somaya says that to allow the work to continue in the other dormitories, it is planned to move students to buildings located on the new campus built in an adjacent area. The campus objectively needed interventions, not only for the damage caused by the violent earthquake of January 2001 but especially for the problems deriving from “original sins” such as the use of poor quality bricks that gave problems to the entire masonry up to the foundations; the experimentation of a consolidation solution which proved extremely harmful carried out by inserting iron rods in vertical holes in the masonry without adequate sealing, which caused the flaking of the brick with oxidation. However, all this is not decisive, as we know well in Venice, a city built entirely of wood and bricks, materials whose defects we know and the great value of being able to be renewed in parts, so much so that in Venice it is not allowed to demolish and reconstruction, but the city continues to offer itself to the visitor’s amazement.

There are other elements to take into account. Between 2001 and 2009 the construction of a second campus was added to the campus as an extension, in a contiguous area, separated by a road that is bypassed by the project to connect the two areas.

The project was drawn up by the architect Bimal Patel, son of art and rising star of the city’s architectural landscape. Together with this information already known, we learn one from the Times of India newspaper this morning (4.1.2021) in which we read that already a couple of years ago the design company ARCOP Associates Private Ltd was assigned to the reconstruction of Kahn’s buildings which is intended to be demolished, so the decision appears to be consolidated well before the Christmas letter. In addition, this assignment is conferred on the basis of a 2014 Master Plan designed by architect Bimal Patel as seen on the HCP website.

This is not the place to deepen the technical details, but before proceeding further with the decision to demolish the IIM dormitories, the cost/benefit ratio of all possible options must be assessed, from restoration to renovation and up to demolition and reconstruction, which in some cases (such as the Venetian one) helps to intervene quickly without getting lost in exhausting debates. There will certainly be someone who can support the inevitability of demolition, but to the local and international community of architecture and art must be given the right to sift and refute the hypothesis that will be proposed.

The case of the IIMA is not an isolated case, there are various precedents and – if the trend is not stemmed – there are serious risks for the future because many others can arrive. Works such as Le Corbusier’s Villa Shodhan could also be at risk, in light of the increase in land values in Ahmedabad which has caused the value of its area to a huge rise. Today the property protects the property it takes care of with respect and attention, but it could at any time give in to the temptation to proceed with the development of the density with demolition and reconstruction with an increase in volume to obtain high profits. In fact, there is no constraint on that extraordinary architecture. It is inconceivable that there are still places that host goods of such importance as to go beyond local and national borders, lacking instruments of protection and guarantee, the world of Culture and local communities must demand that national governments and international institutions adopt appropriate tools regulatory before it’s too late and the damages irreversible.

An example already realized is the project for the riverfront to reduce the Sabarmati riverbed that crosses the city. The intervention was proposed in 1960 with the aim of redeveloping the river (polluted by sewage drains without purification plants) and the banks (in a state of neglect and on which vast slums had settled). It was then modified several times by gradually increasing the volume of building areas justified by the need to finance the intervention. In fact, a questionable idea of development has thus emerged which takes on the characteristics of land speculation to the point of generating new building areas from scratch without taking due account of environmental and landscape issues. The result was the transformation of the river into a channel with a constant width of 263 m. and straight reinforced concrete banks. The need to prevent erosion, control water flows, allocate the sewer system, does not justify the overbuilding of the banks and the absence of any naturalization intervention. The arrangement stands out for its anachronism, it could have been an opportunity to carry out an environmental and ecological intervention to affect the river course, even extra-urban, instead … An opposite indication came from yet another avant-garde masterpiece by Le Corbusier the Millowners Building which presented a refined and highly effective bioclimatic façade device with sunscreen as large as the entire façade, to protect the building from the sun by facilitating the entry of breezes cooled by the water of the river on which overlooked, which then crossed the building cooling it. Also in this case, the damage was caused to the work that lost the relationship with water, taken at a distance by subtracting one of the qualifying factors. Strongly desired by Narendra Modi, then President of the State of Gujarat and today Prime Minister of India, the riverfront design was awarded in 2005 to HCP Design, Planning and Management Pvt. Ltd., a design company headed by Bimal Patel, and was inaugurated on August 15th 2012, Indian Independence Day.

Another controversial case was in 2015 the decision to modify the architectural complex of CEPT, the school of architecture and planning founded by B.V.Doshi, a humble giant of contemporary history, unanimously recognized as a master of architecture and life, was also controversial. Having the good fortune of having the author in good health and still active in the same city, he should have at least been consulted before approaching new buildings with existing ones, modifying the spaces that were an integral and significant part of the original project. A lack of respect that could and should have been avoided. It would be desirable to recognize the copyright on Doshi’s work by placing the consequent constraints, as was the case in the aforementioned case of the Gardellas Condominio Cicogna the Zattere.

In every era, there has been an architect willing to do anything to see his vision realized. In 2015, on the occasion of an exhibition at the Beaubourg on Le Corbusier, a debate opens on the relationship between architects and power taken up among other things on the Espresso columns.

Launched by “l’Obs” and “le Monde”, a debate has sparked in the media and among intellectuals that touches two bare nerves. One concerns the cultural elaboration of pro-fascist and pro-Nazi France, a chapter that is still – sorry to say – minimized. And one is the world of architects, for their ambiguous relationship with regimes. What has prompted many illustrious names of the modern to court authoritarian states and dictatorships: from Le Corbusier to Piacentini, from Speer father and son to Boris Iofan to Philip Johnson, up to now, to Norman Foster and Rem Koolhaas who do business with Arab emirs, Russian oligarchs, the Chinese party-state. Deyan Sudjic, director of the Design Museum in London, calls it “willingness to make agreements of a Faustian type” with the regime in power, “whatever it is”.

Today Indian case also seems to have these characteristics.

Since 2013 CEPT’s President and Executive Director is Bimal Patel, who stands out for his ability to shape Modi’s dreams starting from the public office complex around the Gujarat State Assembly Building in Gandhinagar. His skills are confirmed by the reception in 2019 of the Padma Shri Award after which the assignments for the pharaonic project for the heart of the Indian capital arrived (criticized for the huge sums necessary for the realization and for being of what is called ostentation of vanity), the Mumbai waterfront development, the Kashi Vishwanath corridor in Varanasi.

To the Prime Minister and leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, founded in 1980, is the country’s largest conservative party, a proponent of a nationalist foreign policy and defence of Hindu identity, which intends to reduce the autonomy granted to states border with Pakistan such as Jammu and Kashmir) megalomania, the ostentation of vanity and delusions of grandeur are contested for the great works it promotes, such as:

- The construction of the Ram Mandir temple in Ayodhya, a sacred city of Hinduism linked to the hero rama of the epic Ramayana, costing 123 million euros (1100 crore INR), inaugurated on 5 August 2020.

- The construction of the Gandhi Mandir in Gandhinagar, the capital of Gujarat, with museum and congress centre. The building of the “mausoleum” has the shape of the accumulations of salt enlarged up to the grandeur of the Egyptian pyramids.

- The construction near the great dam on the Narmada river of the largest statue in the world (double the Statue of Liberty) dedicated to Vallabhbhai Patel, a leading conservative exponent of Indian independence first and of the Congress Party later, as Gandhi was a lawyer and native of Gujarat, and like him, he returns to live in Ahmedabad after having practised in Great Britain by settling. Named the Statue of the Union. In 1947 Patel obstructed the division of movable property between India and Pakistan and this was one of the causes of Pakistan’s military vulnerability in those years, a position partially softened following Gandhi’s last fast in January 1948.

- The construction of the redesign of the heart of the capital The Project for the Redevelopment of Central Vista Common Central Secretariat and Parliament in Delhi, the Central Vista axis and the parliament will be completed by 2022 while the Government Palace complex will be completed in 2024).

What is taking place seems to be a conservative and iconoclastic battle, which does not limit itself to selectively re-read history but wants to correct it in a nationalist perspective, overwriting the traces of culturally “foreign” arrangements. A radical turnaround compared to that following Independence which was an approach of positive openness to the most advanced international culture, without prejudice of a geographical or cultural nature.

Living architecture is a lived architecture, not a theory but a participatory practice of a social nature, a positive action of triggering a process that is its product. The process is that of the transformation and adaptation of space as a function of inhabiting (inside a habit/suit), an exercise that concerns the physical and spiritual dimension. The resulting space influences and conditions the wearer in turn, for better or for worse: it can cause well-being (which is not comfort) or discomfort like what one feels when wearing someone else’s dress, which we feel don’t belong to us because it fits too tight, a jacket with short sleeves or oversized long pants. Here, architecture must have a sense of proportion, it is not a display of skill and virtuosity but a humble ability to interpret the spirit of the time, of the places and of the inhabitant who has to wear the suit. In this sense, architecture is a tailored cut tailored to fit the social body and must fit like a skin that changes with us, as we gain weight and lose weight and age and finally go to a better life. Reaching the goal once and for all is impossible, of course, and there is a tendency to make the habit and the monk coincide with the characteristic approximation of intention and tension. The result? habitat, theatre of interactions between living forms, as complex and contradictory as the mystery of life. The space that surrounds us is the mirror of the community that inhabits it, a significant text that we all write and rewrite every day adding happy or unhappy expressions, screaming or just whispered between the lines of pages full of errors, erasures, torn pages. Even without teaching how to read it, one learns to know and appreciate it, of course.

This is the case. The decision to operate changes at CEPT in 2015 provoked protests of today’s students and of those of yesterday, numerous to the point of representing several generations. The case of the Indian Institute of Management is different. In both cases, those who took a stand and asked to be heard were the users, the community of professors, students and researchers, gathered in the Alumni association, but in the second case, they are economics and not architecture specialists. Beyond the outcome of the affair, this will be a source of satisfaction for Doshi, who in addition to IIMA has designed the IIMB, based in Bangalore. On both campuses, nature intentionally insinuates itself almost into the classrooms, to remind those who have to deal with economics that mathematics has the traits of the divine and not just those of profit.

This was also the case at CEPT with the undulating modulation of the ground outside the body of the classrooms where students could lie down experiencing a space of complicity between nature and artifice. Today it has been replaced by an aesthetic arrangement that has removed the ethical component of poetic spaces of service to the training of architects reduced to mere functional spaces.

The mobilizations confirm that the message of those architectures has reached its destination, the awareness that Nature is above all has been involuntarily metabolized, bīja (the seed) is planted and the fertility of its fruits will counteract the aridity of ignorance. Questioning and doubt are the salt of knowledge and educational processes, which are not exclusive to academics or men of power, knowledge does not reside in a classroom but flows through example, the highest form of teaching. Thanks therefore to these communities for having become a critical conscience. We hope that the risk of a senseless demolition will be averted, in any case, the one taking place is a cultural battle worth fighting to build bridges, not walls.

1 / 14

1 / 14

2 / 14

2 / 14

3 / 14

3 / 14

4 / 14

4 / 14

5 / 14

5 / 14

6 / 14

6 / 14

7 / 14

7 / 14

8 / 14

8 / 14

9 / 14

9 / 14

10 / 14

10 / 14

11 / 14

11 / 14

12 / 14

12 / 14

13 / 14

13 / 14

14 / 14

14 / 14

Artribune è anche su Whatsapp. È sufficiente cliccare qui per iscriversi al canale ed essere sempre aggiornati